Built in 1945, the Carpenter Shop is one of the few remaining buildings from the Pittsburgh Plate Glass plant (PPG). With original glass windows made on-site, the shop features panoramic views of the factory ruins. The carpentry crew—made up of around a dozen men—would repair anything in the factory made of wood. Additionally, the carpentry crew built custom wooden crates to transport sheet glass around the world. Having a carpenter shop on-site expedited the shipping process and was more time and cost-effective when machinery broke down. Typical tasks of a carpenter included cutting, working, and joining timber, as well as creating scaffolds for other buildings on-site.

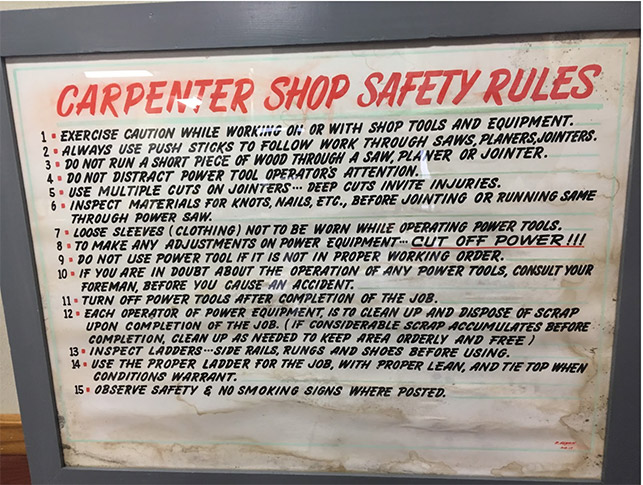

One of the essential jobs of the carpentry crew was making extremely precise maple rulers for the glass cutters. Lloyd Hull, a 31-year employee of PPG, described the carpentry shop as a lively environment, full of both danger and camaraderie. Workers had to adhere to strict rules regarding safety and the operation of shop tools and equipment. Even with proper protocol, accidents still happened—Hull once gashed his hand while operating a mechanical saw. However, the shop had its fair share of good times. Hull recalled that “every once in a while some joker would hang somebody’s long johns from the rafters.” Today, the Carpenter Shop can be rented for small private gatherings.

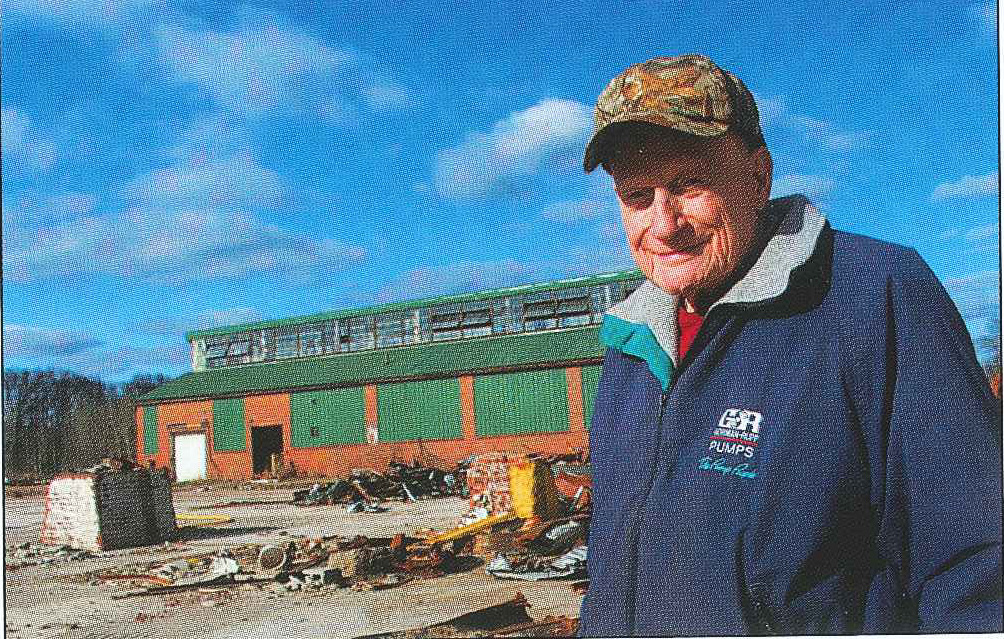

The exterior of the old Carpenter Shop, now the Community Foundation Pavilion. Courtesy of Ariel-Foundation Park

The original windows from the old Carpenter Shop are still intact, providing an ample amount of natural light to the space. Courtesy of Ariel-Foundation Park

Lloyd Hull, a 31-year employee at PPG standing in front of the Carpenter Shop in 2013. Hull spent most of his time in the Carpenter Shop, helping to repair anything in the factory made of wood. Courtesy of Aaron Keirns

This safety sign—now displayed in the Urton Clock House Museum—would have hung in the Carpenter Shop. Image taken by Research Team

Sources

Keirns, Aaron J. Ariel-Foundation Park. Mt. Vernon, OH: Foundation Park

Conservancy, 2015.

"Community Foundation Pavilion." Ariel-Foundation Park. Accessed February 22, 2017. http://www.arielfoundationpark.org/index.php/explore-the-park/community-foundation-pavilion#.